By Leon Zheng, Co-founder & CEO

So… FDA quietly killed one of the anchor documents for SaMD evidence strategy, and a lot of people are still acting like nothing happened. If you build or regulate SaMD, this is not a “meh” housekeeping change.

What actually happened

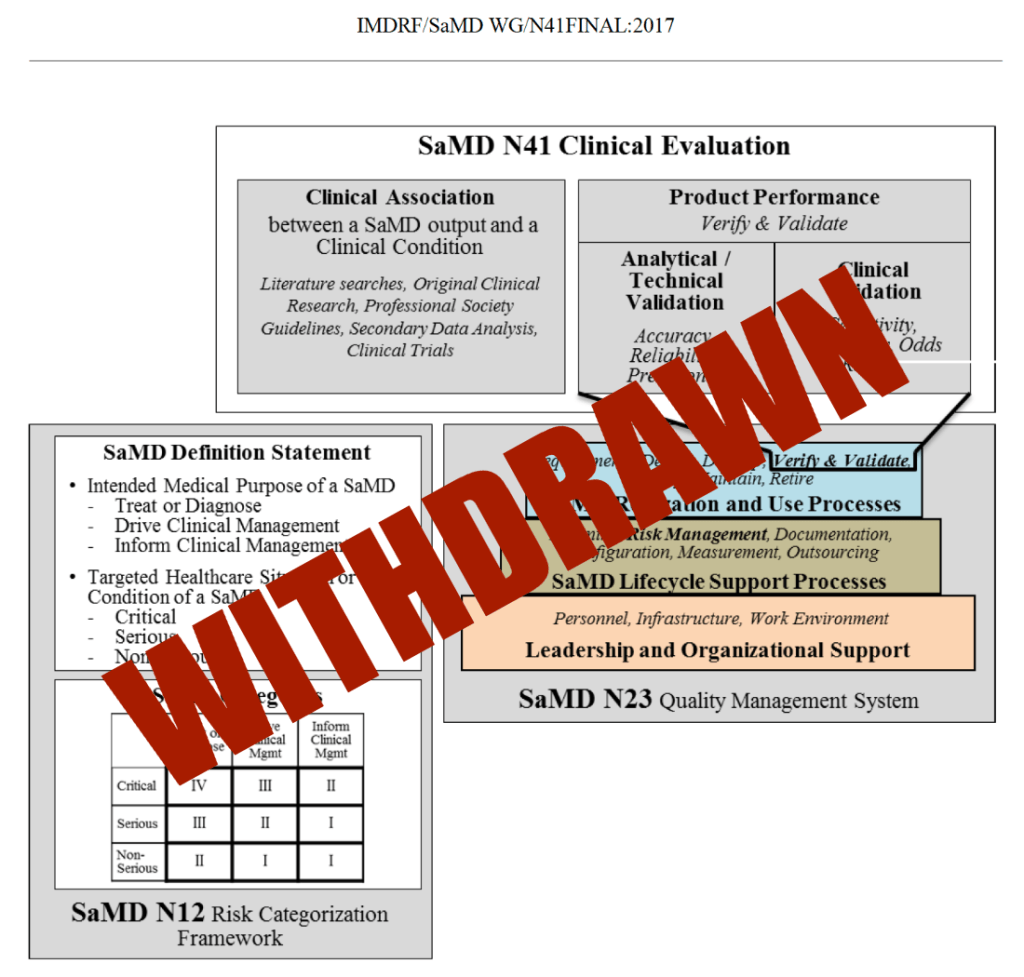

FDA formally withdrew the guidance “Software as a Medical Device (SaMD): Clinical Evaluation,” originally issued in 2017 and based on IMDRF principles.

The withdrawal became effective January 6, 2026, the same day FDA rolled out updated guidances on clinical decision support (CDS) and general wellness products and continued pushing a broader digital health framework.

Practically, this means you can’t cite that guidance as current FDA thinking in submissions, and reviewers are not expected to follow it as a de facto template.

Possible reasons FDA pulled it

FDA hasn’t published a detailed “here’s why we did it” memo, but the move lines up with several trends.

1. Fixed framework vs. fast‑moving software

- The 2017 SaMD guidance described a structured 3‑pillar model (clinical association, analytical validation, clinical validation) that worked well for static or relatively stable software.

- Since then, AI/ML, adaptive algorithms, continuous deployment, and real‑world learning have made rigid, one‑size‑fits‑all templates a poor fit, especially for lifecycle‑managed SaMD.

2. Shift toward risk‑based, contextual oversight

- Recent policy moves (CDS and general wellness updates in 2026, more nuance around “non‑device” CDS, etc.) show FDA trying to distinguish low‑risk digital tools from higher‑risk, decision‑driving software.

- A prescriptive SaMD clinical framework can conflict with that direction, because some low‑risk tools do not need full‑blown, trial‑like evidence, while high‑risk tools may need more than the old model explicitly required.

3. Emphasis on total product lifecycle and real‑world data

- FDA has been leaning into lifecycle oversight for AI‑enabled devices, including guidance on AI device software functions and change management.

- That focus naturally shifts attention from a static premarket “clinical evaluation” document to a more holistic story: premarket data + post‑market monitoring + update processes.

4. Alignment housekeeping with newer digital health guidances

With updated CDS and general wellness guidances now in place (and more AI/ML documents on deck), keeping an older, potentially conflicting SaMD clinical roadmap in force may create more confusion than clarity.iples.

The 2017 SaMD document drew heavily from IMDRF but did not change statutory requirements, submission types, or core evidentiary obligations.

What has not changed for SaMD

This is not a free‑for‑all deregulatory moment.

Existing digital health guidances (CDS, general wellness, AI‑enabled devices, cybersecurity, software lifecycle) remain active and, if anything, are becoming more central to how reviewers frame your submission.

Device statutes and basic requirements for demonstrating safety and effectiveness are unchanged.

510(k), De Novo, and PMA pathways still exist, and reviewers still expect robust, fit‑for‑purpose clinical evidence for higher‑risk SaMD.

Takeaways for SaMD applicants in 2026

For teams planning submissions now, the real question is: “How do we plan clinical evidence without that guidance as our playbook?” Here’s a pragmatic view.

1. Stop treating 2017 SaMD Clinical Evaluation as a safe harbor

- You can still learn from the IMDRF concepts, but you should not present the withdrawn guidance as if it binds the agency.

- Build your justification around current guidances (CDS, general wellness, AI‑enabled device software, cybersecurity, software lifecycle), the FD&C Act, and risk‑based principles, not a withdrawn PDF.

2. Double‑down on risk‑based clinical evidence design

For each SaMD product, explicitly connect:

- Intended use/claims → how much the software influences or drives a clinical decision.

- Risk profile → potential patient harm, failure modes, clinical context (screening vs. diagnosis vs. therapy guidance).

- Evidence package → from bench/algorithm validation up through prospective studies, RWE, or hybrid designs.

Regulators in 2026 are less interested in whether you filled every box in a legacy framework and more in whether the depth and type of evidence are defensible for the risk and claims.

3. Integrate lifecycle controls into your “clinical” story

- For AI/ML and continuously updated SaMD, your clinical rationale should cover: update mechanisms, performance monitoring, trigger criteria for retraining, and how you detect drift.

- Show that post‑market data and surveillance are not an afterthought but a core risk control strategy, especially if you are using real‑world data to refine the model.

4. Write much clearer regulatory narratives

Without a prescriptive guidance to lean on, weak storytelling becomes a liability.

- Explain why your evidence is sufficient and appropriate for your claims and risk profile, using current guidances as anchors, not as checklists.

- Make the link explicit between premarket datasets, validation metrics, and real‑world performance monitoring so reviewers can quickly see that you’ve thought in lifecycle terms.

5. Re‑baseline your internal playbooks and diligence checklists

Update them to align with current digital health guidances and a risk‑based, lifecycle‑oriented approach, and treat the old SaMD framework as historical context, not a rulebook.

If your internal SOPs, templates, or investor/BD checklists literally reference the 2017 SaMD Clinical Evaluation guidance as “the standard,” they are now out of date.

TL;DR for the digital medtech crowd

FDA didn’t lower the bar; it removed a rigid map that no longer fit the terrain. In 2026, winning SaMD submissions are going to come from teams that can justify tailored, risk‑appropriate clinical strategies and show mature lifecycle governance, not from teams that can quote a withdrawn guidance line‑by‑line.moment.

Leave a comment